This is one of those stories of identity, migration, and cultural fusion that best reveal the powerful connection between human memory and taste. When the Japanese enjoy their favorite sweet bun - melonpan - few imagine that its roots reach all the way to Karin, an ancient Armenian city, and that it reached the heart of Tokyo through the hands of an Armenian baker. Behind the crispy crust of melonpan lies the story of a diaspora Armenian family that endured the painful separations of the old world, resilience, and the search for a new homeland.

Image by: Maison Marom

Maison Marom Group of companies has brought melonpan back to its homeland. It can now be tasted in Yerevan - at Rien-à-Porter space (address: 35 Pushkin St.) - becoming part of Japan’s Armenian trace. And what makes this bun so special - you will find out below.

The prehistory of Japanese bread

For a long time, the Japanese didn’t know what wheat was. Bread appeared on their tables only in the 16th century, thanks to Portuguese missionaries. However, during Japan’s period of self-isolation, wheat culture was forgotten - until the mid-19th century, when the country opened up to the world. Along with this opening began a great culinary transformation in Japan. And it was during those turning years that Armenian baker Hovhannes (Ivan) Gevonian–Sagoyan appeared in Tokyo - forever changing the history of Japanese bread.

From Karin to Moscow

Hovhannes Gevonian was born in 1888 in Karin (Erzurum). At the beginning of the 20th century, the persecutions and genocide against Armenians in the Ottoman Empire forced him and his family to flee their homeland.

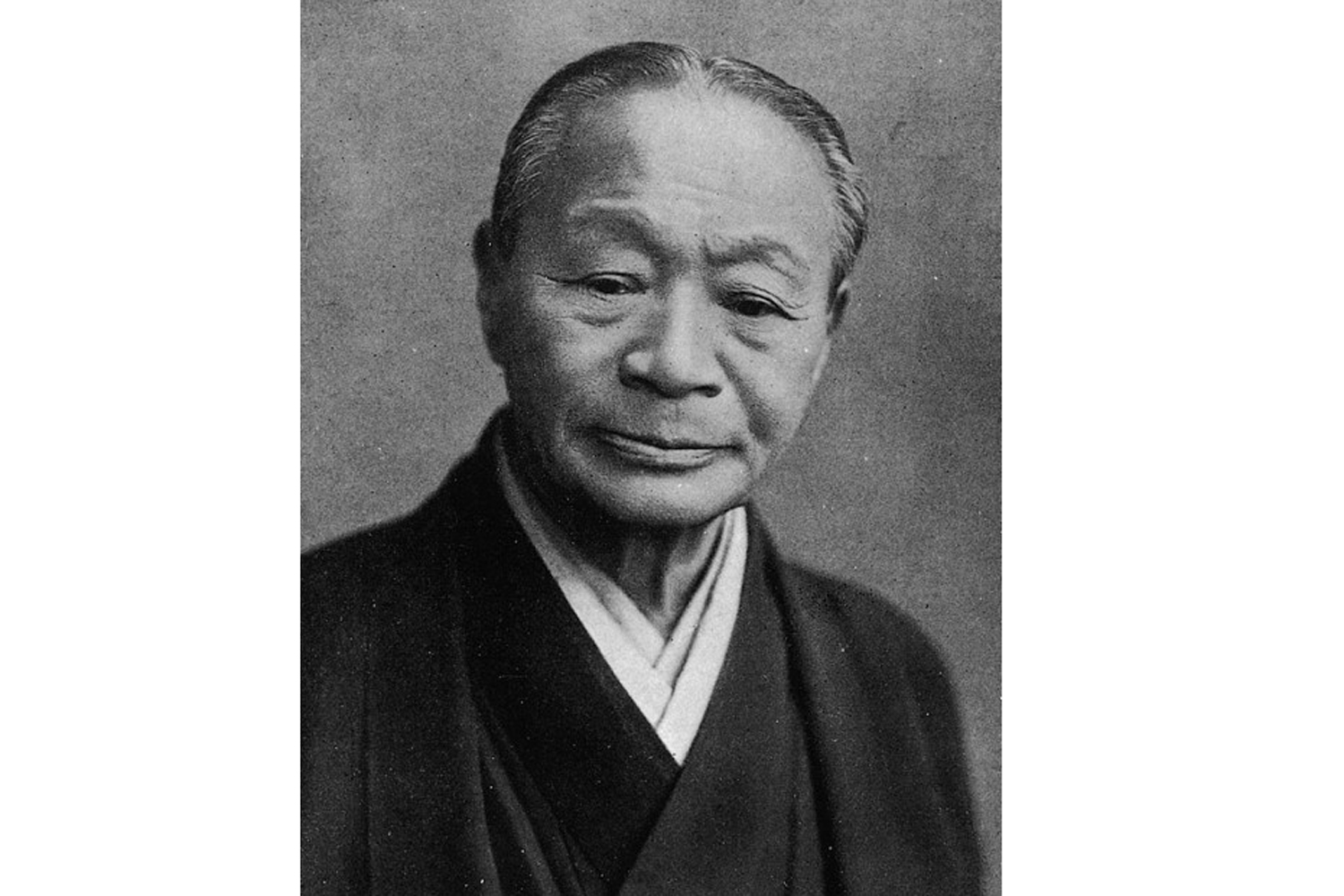

Hovhannes Gevonian

Fate took him to Moscow, where he turned his mastery of baking into an art - becoming a confectioner in the Romanov imperial family. There he learned the delicate styles of French and Austrian confectionery, combining them with the traditions of Armenian pastry-making. It was there that his unique style took shape - precision, delicacy, and love for baking.

The Romanov family

Harbin. A crossroads of destiny

After the Russian Revolution, Gevonian, like thousands of emigrants, found refuge in Harbin - a cosmopolitan city in Manchuria where Russian, Chinese, and Japanese influences intertwined. There he became the head baker of the “New Harbin” hotel, famous for its incomparable bread and sweets.

The city of Harbin

It was there that his fame reached Tokyo industrialist Baron Okura Kihachiro, who wanted to bring him to Japan to form a new bread culture. That invitation became fateful for the future “Monsieur Ivan,” opening a new world before him.

Baron Okura Kihachiro

Tokyo and “Monsieur Ivan”

Upon arriving in Japan, Gevonian began working at Tokyo’s famous “Imperial” hotel, introducing European baking techniques. For the Japanese, all this was a true novelty: soft, fragrant breads and buns with various combinations.

The Imperial Hotel

A few years later, he opened his own bakery called Monsieur Ivan. It was there that what is now known throughout Japan as melonpan was born - a sweet bun, soft inside and covered on top with a crispy biscuit. The name comes from the French expression pain melon, but in fact, the original version had no melon flavor. Later, different varieties were filled with chocolate, cream, or fruity flavors.

Melonpan quickly became popular and loved - not only for its taste but also for its unique character: it united Western pastry-making techniques and Japanese refinement, creating a new cultural bridge.

Image by: Maison Marom

Family and faith. Armenian identity in Japan

Hovhannes Gevonian married Tsuruko Miyakozawa and had three daughters - Kimiko, Evgenia, and Lily. Although they lived in Japan and spoke Japanese, the family remained deeply connected to its Armenian roots.

They attended Tokyo’s St. Nicholas Cathedral, preserving their faith and cultural memory. In 1925, Archbishop Ruben Manasyan of Etchmiadzin baptized their children and solemnized their marriage according to the canons of the Armenian Apostolic Church, preserving their identity on foreign soil.

Legacy and influence on Japanese cuisine

Ivan Sagoyan shaped an entire generation of Japanese bakers. His most famous student was Fukuda Motoyoshi, who later created “hotel bread” - soft, milky bread still eaten daily in Japan.

Sagoyan died in 1952 and was buried in Yokohama’s Foreigners’ Cemetery. On his tombstone it is written:

“With longing for the homeland and with the Armenian spirit” - an expression that perfectly sums up the essence of his life.

Image by: Maison Marom

The symbolic meaning of melonpan

Melonpan is not just a pastry. It is a story - soft on the inside, resilient on the outside. It reminds us of the fate of immigrants - whose hearts always remain warm, even when their lives are covered with a hard layer of new realities.

Melonpan symbolizes the mixture of identities, the strength to adapt, and the idea that food can become a language of memory and love - crossing beyond borders.

Image by: Maison Marom

Academic recognition and mentions

Sagoyan’s story has interested many scholars around the world.

Dr. Haruko Wakabayashi of the University of Tokyo studied the integration of bread into Japanese cuisine, specifically emphasizing Sagoyan’s role.

Armenian diaspora researcher Levon A. Sargsyan considers his life a symbol of the long echo of the genocide.

Harvard professor Julia Smith includes the story of melonpan in studies on food and migration memory.

In 2017, Yukio Watabe published a book - “Ivan’s Bread: The Man Who Became the Foundation of Japanese Hotel Bread,” in which Sagoyan’s life and legacy are presented in detail.

Maison Marom is a group of companies operating in the lifestyle sector, whose mission is “To make business a cultural heritage.”

The group’s activities include three main directions - fashion, gastronomy, art and culture - as well as the development of the lifestyle ecosystem.

Founded in Armenia but operating with an international focus, Maison Marom’s vision is to develop creative industries, promote sustainable entrepreneurship, and form an open cultural ecosystem.

×

×

Comments

Dear visitors, You can place your opinion on the material using your Facebook account. Please, be polite and follow our simple rules: you are not allowed to make off - topic comments, place advertisements, use abusive and filthy language. The editorial staff reserves the right to moderate and delete comments in case of breach of the rules.